When Speech Betrays You: Peter's Denial and the Anatomy of Failure

Study Peter's denial in Matthew 26:69-75: an exegetical exploration of prophecy fulfillment, honor-shame dynamics, speech, and repentance for biblical scholars.

Peter's threefold denial gets taught as a cautionary tale. Don't be like Peter. Don't deny Christ when the pressure's on. Don't overestimate your courage.

But there's so much more happening in this courtyard than a disciple losing his nerve.

I generated a scholarly report on Matthew 26:69-75 through the Anselm Project. The passage is a masterclass in prophecy fulfillment, honor-shame dynamics, and the brutal honesty of early Christian memory.

The Social Architecture of Shame

First-century Mediterranean culture ran on honor and shame. Your reputation was currency. Public accusation wasn't just embarrassing; it threatened your social standing, your economic security, your entire network of relationships.

Peter's sitting in a courtyard. Not a private space. A threshold between public and private where servants and bystanders congregate. Everyone can see him. Everyone can hear him.

A servant girl identifies him. Not a high-status witness. The kind of person whose testimony you might dismiss. Except she's right, and everyone knows it.

"You were with Jesus the Galilean."

That's not just an observation. It's an accusation that links Peter to a condemned man. The report notes that regional identity markers like "Galilean" carried social weight. Speech patterns, accent, mannerisms - all of it marked you. And in a courtyard where Jesus has been arrested, being identified as his follower is dangerous.

Peter denies it. Simple at first. "I don't know what you're talking about."

But the accusations escalate. Another girl. Then bystanders. And here's where the linguistic analysis in the report gets interesting: "Your speech betrays you."

Peter's trying to hide, but his voice gives him away. The Greek suggests phonetic or dialectical markers that exposed his Galilean origin. He couldn't fake being someone else. His identity leaked through his words.

The Escalation of Denial

Peter's second denial includes an oath. His third includes cursing. This isn't just Peter getting more emphatic. It's him deploying the heaviest social and religious artillery he has.

Oaths in the ancient world weren't casual. You invoked divine or communal sanction as proof of truthfulness. Cursing functioned similarly - a performative speech act meant to establish credibility when you had no other evidence to offer.

The report points out that these verbal intensifications were standard in honor-shame cultures. When your word is questioned, you escalate. You swear. You curse. You do whatever it takes to restore your credibility.

And then the rooster crows.

Prophecy, Memory, and the Rooster

The rooster isn't just a time marker. It's a narrative trigger.

Jesus predicted this. "Before the rooster crows, you will deny me three times." Peter probably heard that prediction as hypothetical. Worst-case scenario. Something that wouldn't actually happen.

But the crow converts prophecy into reality. The sound synchronizes Peter's memory with the moment. He remembers what Jesus said. He realizes what he's done.

And he weeps bitterly.

The report notes that this kind of bitter weeping functions as a penitential response in biblical idiom. It's not just regret. It's the visceral, embodied acknowledgment of moral failure. Peter's tears are the first step toward restoration.

Why Early Christians Preserved This Story

Here's what strikes me about this passage: early Christians could have buried it. Peter becomes a foundational leader. The rock. The one who receives the keys. The preacher at Pentecost.

Why preserve a story about him failing so spectacularly?

Because the Gospel writers weren't interested in hagiography. They weren't building mythic heroes. They were recording what happened, even when it was embarrassing. Even when it made their leaders look weak.

The report suggests this episode functions as an instructive exemplum. It models consequences of disloyalty while also creating space for repentance and restoration. The narrative doesn't end with Peter weeping. It ends with Jesus restoring him in John 21.

Failure isn't final. Denial doesn't disqualify you so long as its attached to repentance, and you have to own it. You have to weep over it. And you have to let Christ restore you.

What This Means for Ministry

I've been in ministry long enough to see patterns. People fail. Leaders fail. Sometimes spectacularly. Sometimes publicly.

The question isn't whether failure happens. It's what you do after the rooster crows.

Peter's denial is a gift to the church because it refuses to sanitize discipleship. Following Jesus isn't about perfect courage or unwavering loyalty. It's about recognizing your failure, repenting, and trusting that Jesus can still use you.

The scholarly analysis in the Anselm Project Bible helps see layers. The social dynamics. The linguistic markers. The prophetic structure. But the pastoral takeaway remains simple: even apostles deny Christ under pressure, and even deniers can be restored.

If you want to explore this passage yourself, the report is available in the Share Gallery (for now). The Synod feature also lets you throw theological questions at multiple AI experts for deeper discussion.

Honor-shame dynamics still affect our world. Oaths and curses mattered then; they matter now. Peter's tears are still that; repentance, and the broader biblical patterns of repentance.

But at the end of the day, the story told is about a prominent man who failed, wept, and was restored. And that's a story every pastor needs to preach and sympathize with, because it's a story every Christian needs to hear.

God bless, everyone.

Related Articles

Jerusalem Rejected the Gift

Matthew 2's shocking image of Kings and Priests rejecting God's gift: how worship continued while th...

The Long Road to Bethlehem: Understanding Messianic Prophecy

Explore messianic prophecy as a theological trajectory from Genesis to Revelation, unveiling how pro...

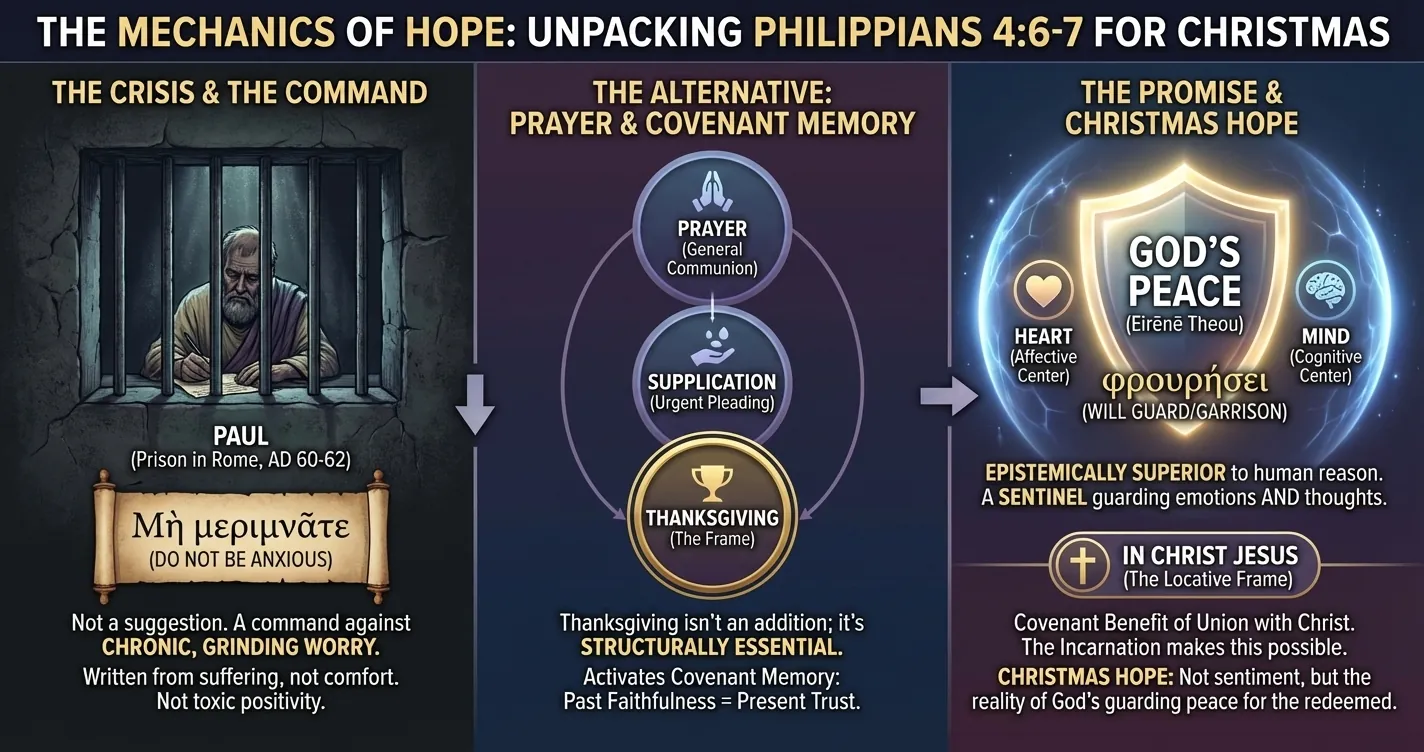

Christmas Time, Hope, and Philippians 4:6-7

Paul's command against anxiety in Philippians 4:6-7 isn't sentimental Christmas hope - it's a theolo...