The Long Road to Bethlehem: Understanding Messianic Prophecy

Explore messianic prophecy as a theological trajectory from Genesis to Revelation, unveiling how promise, liturgy, and kingship shape Christ's coming now.

Every Christmas we hear about prophecy fulfilled. Isaiah 7:14, Micah 5:2, maybe a few others if your pastor is ambitious. We nod along because we know the baby in the manger is supposed to check boxes from the Old Testament.

But messianic prophecy isn't a checklist. It's a centuries-long theological conversation that starts with cryptic promises in Genesis and ends with cosmic visions in Revelation. The trajectory is so complex that it took me over 250,000 tokens of AI analysis just to map it properly through a topical report on the Anselm Project.

What I found wasn't simple prediction and fulfillment. It was promise building on promise, image layering over image, expectation deepening and complicating across twelve centuries of sacred text. The Old Testament doesn't just predict a messiah. It slowly constructs the grammar, the categories, the theological architecture that makes Christ's arrival intelligible.

The Grammar of Promise

Genesis doesn't give us a detailed messianic doctrine. Instead, it gives us what the report calls "the grammar of promise." The seed language in Genesis 3:15, the covenant with Abraham, the blessing of Judah in Genesis 49—these aren't fully formed prophecies. They're foundational vocabulary.

The Hebrew term zeraʿ (seed/offspring) appears throughout Genesis, and it's deliberately ambiguous. It can be collective or singular, a people or a person. That ambiguity is intentional. God's promise is both corporate and individual, national and personal.

When Jacob blesses Judah and says "the scepter shall not depart from Judah...until Shiloh comes" (Genesis 49:10), we're getting royal imagery without a developed royal theology. The shevet (scepter) is there, but the institution of kingship is still centuries away. Genesis is setting up expectations it won't fulfill.

Numbers adds prophetic oracle. Balaam's "star out of Jacob" and "scepter rising from Israel" (Numbers 24:17) gives us cosmic and political imagery. But again, it's promise language, not detailed prediction. The Torah ends with Deuteronomy's prophet-like-Moses expectation, grounding future hope in covenantal obedience and ethical renewal rather than mere political triumph.

From Dynasty to Liturgy

The Davidic covenant in 2 Samuel 7 changes everything. Now we have a concrete dynasty, a bayit (house) that God promises to establish forever. The father-son language, the perpetual throne, the covenant vocabulary—this is where messianic expectation gets institutional grounding.

But here's what's fascinating: Chronicles takes that royal promise and welds it to the temple. The messiah isn't just a political figure in Chronicles. He's a cultic figure whose legitimacy is inseparable from proper worship. First Chronicles 17 and 22 make temple-building central to Davidic succession. The future ruler's authority depends on securing the worship-life of the community.

Then the Psalms turn political expectation into prayer. Psalm 2's anointed son, Psalm 22's suffering vindicator, Psalm 110's priest-king after the order of Melchizedek—these aren't historical records. They're liturgical texts that shape how Israel imagines and prays for the coming deliverer. The royal figure becomes a worshiper's hope, integrated into Israel's devotional life.

The Hebrew term māšîaḥ (anointed one) gets its theological weight from this intersection of dynasty, cult, and liturgy. You can explore these terms more deeply in the biblical lexicon I've built into the site.

The Prophetic Deepening

Isaiah and Jeremiah do something unexpected. They don't just repeat the royal promise. They complicate it.

Isaiah's servant passages introduce vicarious suffering. The servant in Isaiah 42-53 bears corporate guilt, is afflicted, and through that affliction brings justification and healing. This isn't what anyone expected from a royal messiah. Kings conquer. They don't suffer for others.

But Isaiah presents both images: the royal branch from Jesse's root in chapter 11 and the suffering servant in chapter 53. Somehow these are supposed to coexist. The ṣedeq (righteousness) the messiah brings involves both mishpat (justice/judgment) and substitutionary suffering.

Jeremiah adds the new covenant motif. In Jeremiah 31, the future restoration isn't just political. It's heart-transformation, internalized Torah, corporate forgiveness. The Davidic branch in Jeremiah 23 will reign righteously, but that reign presupposes a people with transformed hearts.

Ezekiel and Zechariah keep building. Ezekiel's shepherd-prince in chapter 34 combines pastoral care with royal authority. Zechariah's priest-king in chapter 6 merges cultic and political functions in ways the Torah never explicitly authorized. The humble king on a donkey in Zechariah 9 subverts martial expectations entirely.

By the time you get to Daniel, you have apocalyptic imagery—the bar enash (son of man) figure receiving cosmic dominion from the Ancient of Days. Messianic expectation has moved from tribal blessing to royal dynasty to cultic mediator to cosmic judge.

The Fulfillment Pattern

Matthew's Gospel opens with "this was to fulfill what was spoken by the prophet" and that formula appears throughout. But Matthew isn't just proof-texting. He's showing how Jesus embodies and reinterprets the entire trajectory.

The virgin birth fulfills Isaiah 7:14 in Matthew 1. The Bethlehem birthplace fulfills Micah 5:2 in Matthew 2. The Hosea 11:1 citation—"out of Egypt I called my son"—treats Jesus as recapitulating Israel's story. Matthew is reading Israel's Scripture typologically, seeing patterns that find their culmination in Christ.

Luke does the same thing with a pastoral emphasis. When Jesus reads Isaiah 61 in the Nazareth synagogue and says "today this Scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing," he's claiming that the prophetic trajectory converges on his ministry to the poor, the captive, the blind.

The apostolic preaching in Acts constantly appeals to Davidic psalms. Peter at Pentecost, Paul at Pisidian Antioch—they read Psalm 16 and Psalm 110 as predictive of resurrection and exaltation. The anastasis (resurrection) becomes the decisive proof that Jesus is the promised Christ.

The Theological Architecture

What I find compelling is how the New Testament writers don't just cite isolated verses. They're working with the entire canonical architecture.

Paul in Galatians 3 zeroes in on the singular sperma (seed) of Abraham to identify Christ as the covenant heir. He reads the curse-bearing of Deuteronomy 21 through Christ's crucifixion to explain redemption. The Spirit-gift becomes the Abrahamic blessing extended to Gentiles.

Hebrews takes the Melchizedek priesthood of Psalm 110 and builds an entire Christology around superior priesthood and final sacrifice. The author reads the old covenant sacrifices as skia (shadows) pointing forward to Christ's teleios (perfect/complete) offering.

Revelation synthesizes everything. The slain Lamb who is the Lion of Judah, the Son of Man with eyes of fire, the rider on the white horse—John is pulling together Danielic, Isaian, Davidic, and sacrificial imagery into a cosmic portrait of the victorious Messiah who rules through sacrificial love.

Why This Matters at Christmas

When we sing about Emmanuel and the newborn King, we're celebrating the convergence of a multi-century prophetic trajectory. The child in the manger is the seed promised in Eden, the blessing to Abraham's offspring, the scepter from Judah, the prophet like Moses, the Davidic heir, the suffering servant, the priest-king, the son of man.

But he's all of these in unexpected ways. He conquers through weakness. He reigns through service. He establishes justice through suffering. He mediates worship through self-offering. He brings the kingdom through cross and resurrection.

The prophecies weren't wrong. They were incomplete. Each prophet saw part of the picture. The Torah gave grammar. The histories gave dynasty. The Psalms gave liturgy. The prophets gave suffering and scope. Daniel gave cosmic vindication. But only the incarnation, crucifixion, and resurrection bring all of it together into a coherent whole.

This is why I love working on the Anselm Project Bible. Translating directly from Hebrew and Greek forces you to sit with these texts in their original languages, to see the connections the English sometimes obscures. Terms like māšîaḥ, zeraʿ, berît, ṣedeq—they create a theological vocabulary that develops across the canon.

I've shared some reports on messianic themes in the Share Gallery if you want to see how the AI analysis handles these connections. The mixture-of-experts approach lets different specialized perspectives examine the same prophetic texts and show how they interact.

The Patience of God

What strikes me most about messianic prophecy is God's patience. He could have sent the Messiah in Genesis 4. He could have detailed everything to Moses. He could have given David the full picture.

Instead, he let the expectation develop slowly across centuries. Each generation received enough light to hope and trust, but not enough to presume. The promise stayed constant—God will save his people—but the shape of that salvation emerged gradually.

By the time Mary says "let it be to me according to your word," the stage is set. The grammar is in place. The royal line is established. The prophetic vision has been articulated. The psalms have taught Israel to pray for a suffering-yet-vindicated deliverer.

And then God does something more glorious than anyone imagined. The Word becomes flesh. The promise becomes person. All the types and shadows give way to substance.

That's the scandal and glory of Christmas. Not that God fulfilled prophecy in some mechanical, checklist way. But that he took centuries of promise and brought them to fruition in a way that exceeded and reinterpreted every expectation.

The long road to Bethlehem wasn't a straight line. It was a winding path through patriarchal tents, Davidic palaces, exilic laments, and apocalyptic visions. But every step was God's sovereign direction toward the moment when heaven and earth would meet in a feeding trough.

God bless, everyone.

Related Articles

When Speech Betrays You: Peter's Denial and the Anatomy of Failure

Study Peter's denial in Matthew 26:69-75: an exegetical exploration of prophecy fulfillment, honor-s...

Jerusalem Rejected the Gift

Matthew 2's shocking image of Kings and Priests rejecting God's gift: how worship continued while th...

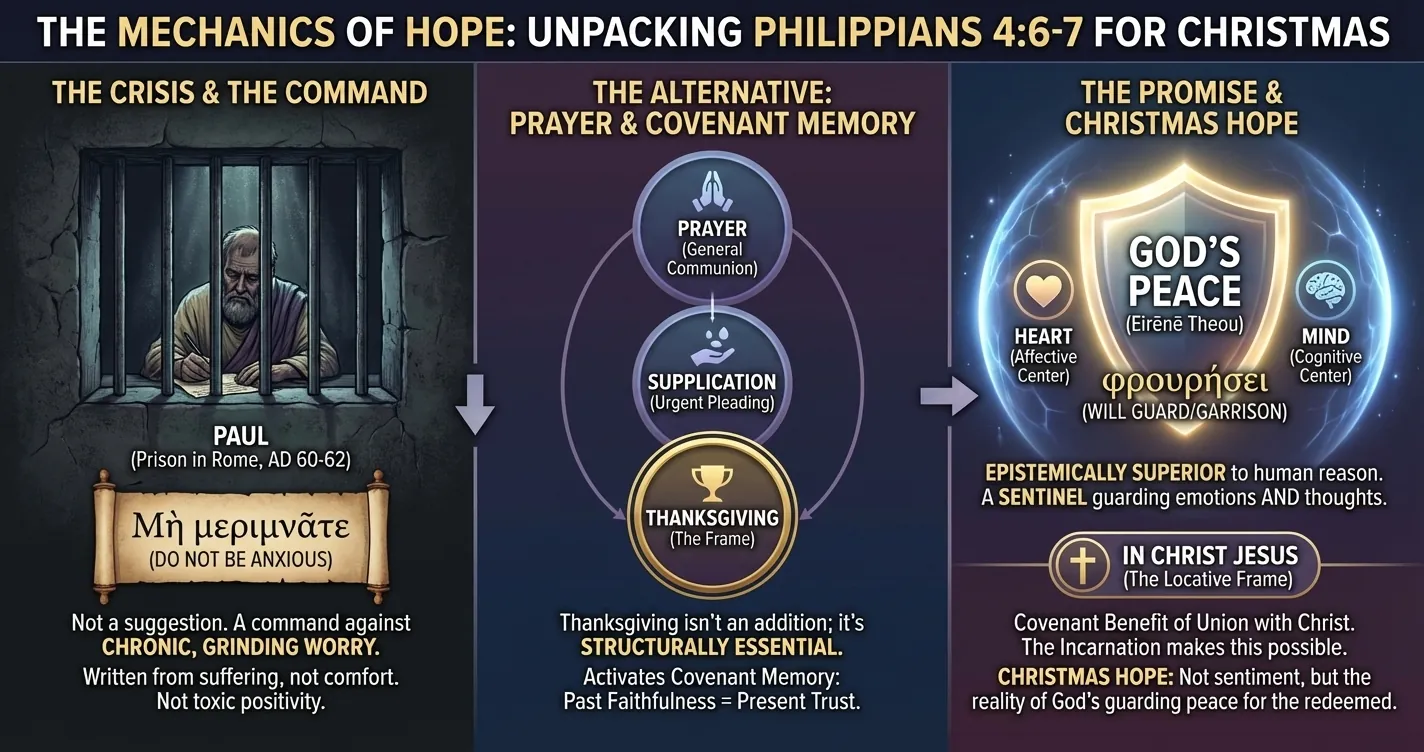

Christmas Time, Hope, and Philippians 4:6-7

Paul's command against anxiety in Philippians 4:6-7 isn't sentimental Christmas hope - it's a theolo...