John the Baptist: Hinge of Covenant — Covenant Transition, Baptismal Theology, and Prophetic Authority

Considering John the Baptist as the redemptive-historical hinge between old and new covenants, unpacking baptismal theology, prophetic authority, and eschatology.

I spent some time this week working through John the Baptist, and the more I study him the more convinced I am that you cannot properly understand the transition from old covenant to new covenant without grappling with his ministry. He's not peripheral. He's the redemptive-historical hinge on which the entire biblical narrative turns from promise to fulfillment.

That positioning matters for how we read both Testaments.

Covenant Transition and Prophetic Authority

John the Baptist was born into a priestly family during the late Herodian period. His father Zechariah served in the temple, his mother Elizabeth descended from Aaron. By bloodline and birthright, John belonged to the cultic establishment of Second Temple Judaism. He should have followed his father into temple service, perpetuating the sacrificial system that had defined Israelite worship for centuries.

Instead, he went to the wilderness.

That choice was not aesthetic or arbitrary. John's wilderness location and ascetic lifestyle deliberately positioned him outside the temple establishment and in continuity with Israel's prophetic tradition, particularly Elijah. When Isaiah 40:3 speaks of "a voice crying in the wilderness, 'Prepare the way of the Lord,'" the wilderness is not incidental geography. It represents the place of covenant renewal, where Israel met God during the Exodus, where prophets went to hear God's word unmediated by institutional religion.

John's wilderness preaching therefore carried an implicit critique: the temple establishment had become inadequate for the eschatological moment at hand. The sacrificial system continued, the priests still offered lambs, but something fundamental was missing. Real preparation for God's inbreaking kingdom required more than ritual compliance. It required ethical transformation and covenant renewal from the heart.

Baptismal Theology and Eschatological Repentance

John's baptism marks a significant innovation in Jewish practice. While ritual washings existed in Second Temple Judaism, John's baptism differed in crucial ways. It was administered once, not repeated. It was public, not private. And most importantly, it explicitly linked ritual washing with moral repentance in preparation for imminent eschatological judgment.

When John confronted the Pharisees and Sadducees who came for baptism, calling them a brood of vipers, he exposed the insufficiency of ethnic covenant identity apart from ethical transformation. "Do not presume to say to yourselves, 'We have Abraham as our father,'" he warned them. That rebuke strikes at the heart of Second Temple Jewish identity. Abrahamic descent had functioned as covenant security, but John insisted that the coming judgment would evaluate fruit, not lineage.

This represents a radical reconfiguration of covenant membership. John's baptism functioned as a kind of eschatological sorting mechanism, dividing true Israel (those who repented and bore ethical fruit) from nominal Israel (those who presumed on ethnic privilege without transformation). The crowds who came to be baptized were effectively acknowledging that their existing covenant status was insufficient for what was coming.

But John's baptism was also inherently provisional. He himself distinguished it from the baptism the coming one would administer: "I baptize you with water for repentance, but he who is coming after me is mightier than I... he will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire." Water could mark repentance, but it could not effect the deeper transformation only the Spirit could accomplish. John could call for ethical renewal, but he could not impart the new covenant gift of the indwelling Spirit that Ezekiel had promised.

This is why Acts carefully distinguishes between those baptized only with John's baptism and those baptized into Christ. Paul encounters disciples in Ephesus who had received John's baptism but knew nothing of the Holy Spirit. After explaining that John's baptism pointed forward to Jesus, Paul baptizes them in Jesus' name and they receive the Spirit. John's baptism prepared the way, but Christian baptism inaugurates participation in the new covenant reality Christ accomplished.

Christological Witness and Typological Fulfillment

The baptism of Jesus by John represents the theological climax of John's ministry. When Jesus came to the Jordan requesting baptism, John's initial resistance was theologically appropriate. If John's baptism was for sinners needing repentance, why would the sinless one submit to it? Jesus' insistence that this was necessary "to fulfill all righteousness" points to something deeper than personal need for repentance.

Jesus' baptism functioned as his public identification with Israel and as the inauguration of his messianic office. By submitting to John's baptism, Jesus positioned himself as the representative Israelite who would accomplish what Israel failed to accomplish. He entered the waters of judgment on behalf of his people, and when he emerged, the Spirit descended and the Father's voice authenticated him as the beloved Son.

John's witness to this event is crucial. He saw the Spirit descend and remain on Jesus, and he heard the divine testimony. Afterward, when John publicly identified Jesus as "the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world," he was making a profound theological claim that synthesized multiple Old Testament trajectories.

The Lamb imagery evokes the Passover lamb whose blood marked Israelite households for deliverance from judgment. It recalls the daily tamid offerings in the temple where lambs were sacrificed morning and evening for Israel's sins. It points to Isaiah 53, where the suffering servant is led like a lamb to slaughter and bears the iniquities of the people. John was declaring that Jesus would accomplish what all those lambs only symbolized: actual removal of sin through substitutionary sacrifice.

This identification also clarifies John's typological relationship to Christ. John announced and prepared, but Christ accomplished. John baptized with water, but Christ baptizes with the Spirit. John pointed to the Lamb, but Christ is the Lamb. John called for repentance from sin, but Christ bears sin and removes it. The pattern is consistent: John's entire ministry exists to highlight Christ's supremacy and uniqueness by showing what only Christ can do.

When some of John's disciples expressed concern that Jesus' ministry was attracting larger crowds, John responded with theological clarity rather than competitive anxiety: "He must increase, but I must decrease." This was not false humility or ministerial politeness. It was accurate covenant theology. John understood that his role as forerunner meant preparing hearts and then stepping aside. The friend of the bridegroom rejoices when the bridegroom arrives and takes his bride. John's joy was complete precisely because Jesus was now taking center stage.

Prophetic Suffering and the Cost of Covenant Fidelity

John's martyrdom under Herod Antipas was not incidental to his prophetic office but intrinsic to it. When John publicly rebuked Herod for his illicit marriage to Herodias, his brother Philip's wife, he was functioning in the classic prophetic role of confronting covenant violation at the highest levels of power. The prophets of Israel repeatedly paid this cost. Elijah fled from Jezebel. Jeremiah was imprisoned. Zechariah son of Jehoiada was stoned in the temple court. Jesus himself would later say that Jerusalem kills the prophets and stones those sent to her.

John's imprisonment and execution fit this pattern, but they also function typologically. Just as John prepared the way for Jesus' public ministry, so John's suffering and death foreshadowed Jesus' own rejection, suffering, and execution. Both men spoke divine truth in a context hostile to that truth. Both threatened existing power structures. Both died as the price of faithful witness.

The manner of John's death carries additional theological weight. Herodias's manipulation of her daughter Salome to request John's head demonstrates the kind of political evil that characterizes fallen human power. Herod Antipas, who had been troubled by John's preaching and who recognized John as a righteous and holy man, nevertheless capitulated to political pressure and expedience. The execution of an innocent man to preserve face and honor a reckless oath reveals the deep corruption of authority structures operating apart from God's justice.

Jesus' evaluation of John is instructive: "Among those born of women there has arisen no one greater than John the Baptist. Yet the one who is least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he." This statement locates John at the apex of the old covenant order while simultaneously distinguishing that order from the new covenant reality. John's greatness lay in his prophetic calling and his faithful execution of that calling, even unto death. But the kingdom Jesus inaugurates represents a qualitative shift, not merely a quantitative improvement. The new covenant provides what the old covenant anticipated: direct access to God through the Spirit, participation in Christ's resurrection life, and the indwelling presence of God.

John died on the old covenant side of that transition. He prepared hearts for what he himself would not live to experience in its fullness. That position makes his faithfulness even more remarkable. He served a kingdom he glimpsed but did not enter, pointed to a fulfillment he announced but did not receive, and suffered for a truth that would vindicate him only after his death.

Ecclesiological and Pastoral Implications

John's ministry establishes several theological principles that remain normative for the church. First, the distinction between water baptism and Spirit baptism shapes how we understand Christian initiation. The New Testament consistently maintains that John's baptism was provisional and preparatory, while Christian baptism in Jesus' name marks participation in Christ's death and resurrection and the reception of the Holy Spirit. This is why the book of Acts shows apostles rebaptizing those who had only received John's baptism. The church does not merely continue John's ministry with minor adjustments. The church administers the sacrament of the new covenant, which incorporates believers into the body of Christ through the work of the Spirit.

Second, John models the proper relationship between ministry and Christ. All Christian ministry exists to point people to Jesus, not to the minister. John's deliberate self-effacement, his refusal to allow his movement to become an end in itself, and his active redirection of his own disciples toward Jesus establish the pattern for pastoral ministry. The moment ministry becomes about platform-building, influence-gathering, or personal legacy, it has departed from the Johannine model. Faithful ministry decreases so Christ may increase.

Third, John's prophetic critique of religious formalism without ethical substance addresses a perennial temptation in the church. The Pharisees and Sadducees possessed all the external markers of covenant faithfulness: they knew Scripture, they maintained traditions, they participated in temple worship. But John saw through the externals to the absence of genuine repentance and transformation. The church in every age faces the same danger of ritualism without reality, orthodoxy without orthopraxy, confessional correctness without covenant faithfulness. John's baptism demanded visible fruit in keeping with repentance, and the church's sacraments likewise must not become divorced from ethical transformation.

Fourth, John's costly obedience establishes that prophetic witness may require suffering. He could have moderated his message, avoided confronting Herod, or sought political protection. Instead, he spoke truth and accepted the consequences. The church has often domesticated Christianity into a comfortable religion that promises blessing without cross-bearing, but John's ministry contradicts that. Faithfulness to God's word in a fallen world will generate opposition, and disciples must be prepared to count the cost.

Canonical Interpretation and Gospel Perspectives

The four Gospels present John the Baptist with different emphases that together create a theologically rich portrait. The Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke) portray John primarily as the prophetic forerunner who fulfills Isaiah 40:3 and Malachi's messenger prophecy. They emphasize his wilderness preaching, his baptismal ministry, his ethical demands, and his identification of Jesus. Matthew particularly highlights John's confrontations with religious leaders and Jesus' interpretation of John as the Elijah figure. Luke provides the most detailed infancy narrative, establishing John's miraculous birth and priestly lineage, and carefully paralleling John's story with Jesus' story to show their interconnected vocations.

The Fourth Gospel takes a different approach. John the Evangelist uses John the Baptist primarily as witness and testimony. From the prologue's declaration that "There was a man sent from God, whose name was John. He came as a witness, to bear witness about the light," the Fourth Gospel frames John the Baptist's entire purpose as pointing to Jesus. The Fourth Gospel includes extended testimony from John about Jesus' identity, records John's explicit denial that he is the Christ, and emphasizes John's self-understanding as the friend of the bridegroom who must decrease.

This canonical diversity is theologically significant. The multiple perspectives prevent reductionism and force readers to hold together different aspects of John's ministry. He is simultaneously the Elijah-like prophet calling Israel to repentance, the priestly figure whose birth narrative parallels Jesus', the eschatological herald announcing the kingdom's arrival, and the paradigmatic witness whose testimony authenticates the Messiah. Each Gospel writer selects and emphasizes material that serves his particular theological purposes, but together they present John as the redemptive-historical hinge between promise and fulfillment.

The prophetic quotations applied to John are particularly important. Isaiah 40:3 speaks of preparing the Lord's way, which the Gospels apply to John's ministry. This creates an implicit identification: if John prepares the way for the Lord (Yahweh), and John prepares the way for Jesus, then Jesus is identified with Yahweh. The logic is subtle but theologically profound. Similarly, Malachi's prophecy about the messenger sent before the Lord is applied to John, and Jesus himself identifies John as the Elijah figure Malachi promised. These prophetic connections situate John within the larger story of God's redemptive purposes and establish his ministry as divinely ordained rather than merely human initiative.

John's Enduring Theological Significance

John the Baptist occupies a unique position in redemptive history that makes him perpetually relevant for Christian theology and practice. He stands at the boundary between two covenants, embodying the climax of prophetic witness while heralding the arrival of messianic fulfillment. That boundary position creates theological tension that the church must navigate in every generation.

The old covenant was not arbitrary or dispensable. It was God's gracious provision for Israel, given at Sinai and maintained through centuries of prophetic ministry, temple worship, and covenant faithfulness. John represents the perfection of that order. He is the last and greatest of the prophets, the one who brings the entire prophetic trajectory to its appointed end by identifying the Messiah and calling Israel to prepare for his arrival. Yet John's very greatness under the old covenant demonstrates its fundamental insufficiency. He could prepare hearts but not transform them. He could baptize with water but not impart the Spirit. He could announce the Lamb but not provide the actual sacrifice that would remove sin.

This pattern of pointing-beyond-itself characterizes the entire old covenant, and John embodies that pattern in its clearest form. The sacrificial system pointed to the need for atonement but could not actually remove sin (Hebrews 10:1-4). The law revealed God's righteousness but could not empower obedience. The prophets called Israel back to covenant faithfulness but could not give the new heart Ezekiel promised. John the Baptist, as the culmination of that system, shows both its genuine value and its necessary incompleteness.

The church exists on the other side of the boundary John marks. We have received what John announced: the Spirit has been poured out, the new covenant has been inaugurated, the Lamb has been slain and raised. But the church faces a constant temptation to retreat from new covenant reality back into old covenant patterns. We are tempted to substitute ritual for transformation, to rely on religious performance rather than Spirit-wrought renewal, to measure faithfulness by external markers rather than fruit of the Spirit.

John's ministry confronts these temptations. His rebuke of the Pharisees and Sadducees who came for baptism without repentance applies equally to Christians who assume covenant privileges without covenant faithfulness. His insistence that Abraham's children must bear fruit in keeping with repentance warns against presuming on grace while persisting in sin. His distinction between water baptism and Spirit baptism reminds the church that sacraments become empty forms apart from the spiritual reality they signify.

At the same time, John's subordination to Christ establishes the proper relationship between proclamation and reality, between witness and object of witness. The church's preaching, like John's, must always point beyond itself to Jesus Christ. The moment the church becomes an end in itself rather than a pointer to Christ, it has ceased to be faithful. John's example of sending his own disciples to Jesus, of decreasing so Christ might increase, models what faithful ecclesiology looks like.

If you're preparing to preach or study passages involving John the Baptist, you can generate detailed passage reports that explore the theological depth of texts like Matthew 3, Luke 1, or John 1. The Anselm Project Bible presents these passages in their full literary context, and the Share Gallery includes examples of how others have worked through related texts.

Conclusion

John the Baptist did not accomplish redemption. He prepared people to receive the one who would. He did not baptize with the Spirit. He baptized with water and pointed to the one who would baptize with the Spirit. He did not remove sin. He identified the Lamb who would take away the sin of the world.

That preparatory, pointing function is not a deficiency. It is the exact role God appointed him to fulfill. John's entire ministry demonstrates what faithful covenant service looks like: speaking God's word without compromise, preparing hearts for God's work, and directing all attention to Jesus Christ.

The church in every generation needs to recover that Johannine understanding of its vocation. We are witnesses, not saviors. We are heralds, not the kingdom itself. We point to Christ, we do not replace him. And like John, we may find that faithful witness costs us something. But the cost is worth bearing, because the one to whom we point is worthy of all praise, honor, and glory.

God bless, everyone.

Related Articles

Jerusalem Rejected the Gift

Matthew 2's shocking image of Kings and Priests rejecting God's gift: how worship continued while th...

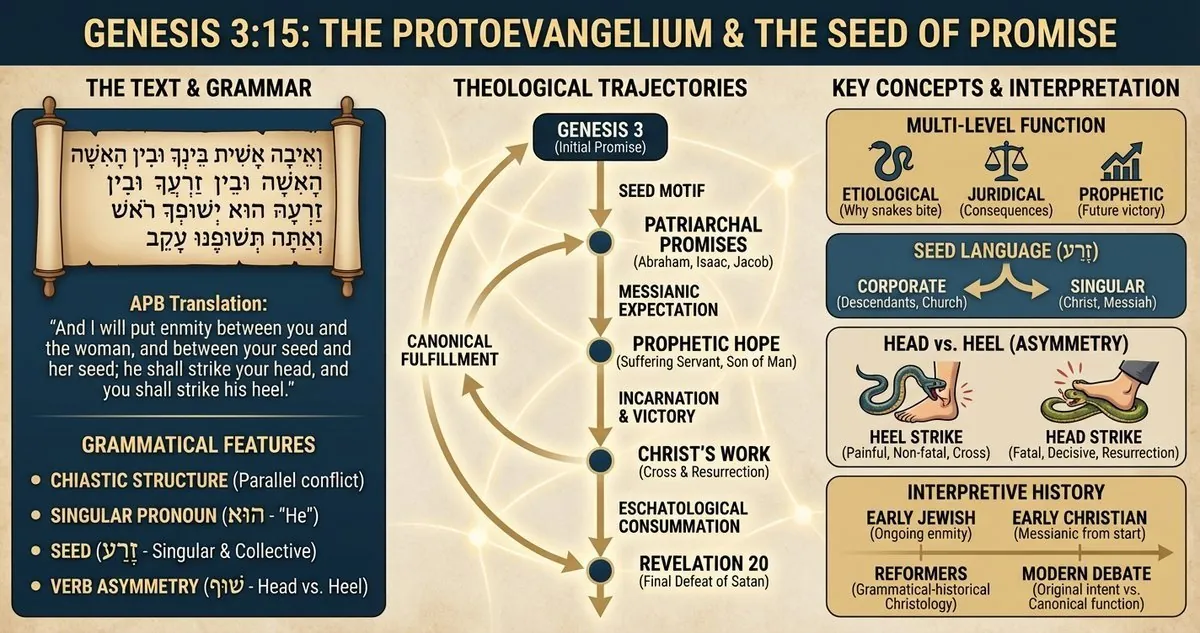

Genesis 3:15 Explained: Protoevangelium, Hebrew Grammar, and Messianic Seed

Explore Genesis 3:15 as the protoevangelium with grammatical, theological, and canonical readings th...

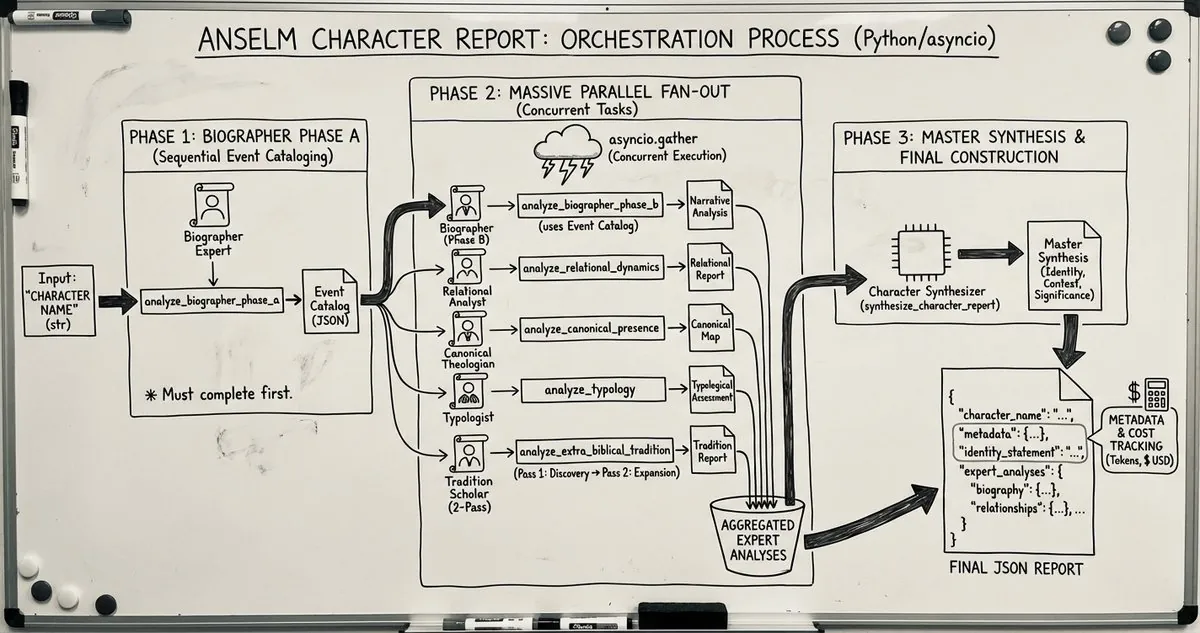

How the Anselm Project Builds AI-Powered Biblical Character Studies

Anselm Project builds AI-powered biblical character studies with a five-expert system, phased workfl...